Generalised Anxiety Disorder

Most parents are familiar with having to soothe their child’s worries about starting school, making friends, taking a test or losing a pet. Feeling anxious about something is a normal human reaction that can actually help us by motivating us to deal with new challenges (Strack et al., 2017) or think twice before engaging in risky behaviours (Hartley & Phelps, 2012).

The problem arises when anxiety becomes pervasive. Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) refers to excessive and uncontrollable worry about a variety of events, meaning that individuals with GAD worry more than is necessary and find it hard to stop worrying. Their experiences can have a debilitating effect - the criteria used to diagnose GAD in Australia specifies that the experience of anxiety impairs an individual’s functioning, whether that be social, occupational or other (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

GAD is common across all age groups, including children and the elderly. In Australia, nearly 6 percent of people will experience GAD in their lifetime (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008) while 2.3 percent of Australian youth met GAD criteria within the previous 12 months (Spence et al., 2018).

Alongside the anxiety itself, a key characteristic of GAD is the presence of symptoms - physical responses, thought patterns, emotions and behaviours - related to being worried. The feeling of anxiety is part of our fight-or-flight-or-freeze response, which is our body’s way of being prepared for danger. When a threat is detected, our autonomic nervous system is activated and begins sending chemical signals to various parts of the body in order to maximise preparedness (Centre for Clinical Interventions, 2019).

People with GAD are constantly being primed for fight or flight or freeze. As a result, they often experience muscle tension due to their muscle groups receiving signals to contract, as well as a general sense of fatigue because their body is in this perpetual state.

The fight-or-flight-or-freeze response also affects our mood and cognition. People with GAD may feel irritated or restless or have trouble sleeping because their body is telling them to confront or escape the “danger”, but their current circumstances prevent them from doing so. They can also experience difficulty concentrating or feel as though their mind is blank because the fight-or-flight-or-freeze response redirects their attention to their surroundings in order to search for potential threats.

While the main features of GAD are present in all individuals with the disorder regardless of age, they can look different in different age groups. This is because developmental changes in physiology and cognition affect the way anxiety and its symptoms manifest.

Recommended Online Course

What does GAD look like in children?

The essential feature of GAD is worry, which is commonly defined as “a chain of thoughts and images, negatively affect-laden and relatively uncontrollable” (Brosschot & Verkuil, 2013). Worry is when our thoughts seem to go around in circles in our heads and we can’t seem to stop them. Importantly, worry is a form of problem-solving - an attempt to determine the outcome of an issue where the outcome is uncertain, but it includes negative possibilities. Most of the research on worry has focused on adults, but recent studies have begun to reveal that children may differ from adults in terms of how they worry and what they worry about.

Most adults are familiar with worry thoughts being verbally expressed, such as through a string of “what if?” questions. However, the ability to represent thoughts with language is dependent on the language skills we have. Studies of primary school-aged children suggest that they spend approximately equal amounts of time worrying in words and in images (Wilson, 2020). They also associate worry more closely with fear - a feeling - than with thinking (Szabo & Carr, 2015). This differs from the way adults and adolescents worry, which is primarily in words and is differentiated from fear.

Another feature of worry is the generation of numerous possibilities. When we worry, we come up with many different outcomes to a single scenario. If a loved one is late coming home, we may worry that they got lost or were in an accident. This feature increases with age as young children often struggle to anticipate future events and may find it difficult to imagine multiple negative outcomes (Songco et al., 2020). This means that children tend to worry about things that make them feel bad and that they avoid (Szabo, 2007), while adults tend to have more abstracted worries that are less associated with negative feelings.

Because children’s verbal and cognitive skills are still in development, GAD often looks different in children compared to adults. Children often present with more somatic issues, such as stomach complaints or headaches, than explicitly expressed anxieties (Anxiety Canada, n.d.). They tend to worry about issues that are closer to home, such as school or sporting performance (APA, 2013). Additionally, children’s capacity to express their worries depends on their level of development. As a result, some children might describe specific things that are worrying them while others might simply say that they “feel bad” or “need to get away”.

Further Reading

How can I tell if my child has GAD?

GAD diagnosis in children can sometimes be tricky. Because the way children feel and show anxiety changes with age, it can be difficult to determine if an anxious child has GAD or a different anxiety disorder. In fact, it is common for children to show symptoms of multiple anxiety disorders.

Key signs of GAD can be found across several areas of cognition, behaviour and daily functioning.

Thoughts

Children with GAD worry about things that are happening in their life, things that could happen in the future and things others would consider to be minor (Anxiety Canada, n.d.). Critically, they worry more than their peers, are worried more days than not and find it hard to stop worrying.

Some typical worries can look like:

- What if I fail my maths test tomorrow?

- What if I lose my soccer game on the weekend?

- What if I don’t find a friend to play with at lunchtime?

- What if my dog gets sick and dies?

- What if we lose all our money and we can’t afford our house?

- What if the COVID-19 pandemic keeps getting worse?

Very young children may not be able to articulate specific worries. Instead, their experiences may be reflected in how they feel, both physically and mentally.

Physical symptoms

GAD involves frequent activation of the body’s fight-or-flight-or-freeze response. This means that children will show a range of physical feelings alongside - or in some cases, instead of - their verbal expressions of anxiety.

These feelings can include:

- Being restless, fidgety or “keyed up”

- Irritability

- Getting tired easily

- Having headaches or stomach aches

- Muscle pain, particularly in the neck and shoulders

Emotions

As well as the obvious emotion of anxiety, children with GAD can show other feelings associated with being worried, including:

- Sadness

- Anger

- Shame

- Guilt

- Fear

Behaviours

Children with GAD often behave in ways that are related to the negative thoughts, emotions and physical feelings they are experiencing. Behaviours may be more internally focused or they may involve instances of acting out or aggression.

Common behaviours include:

- Difficulty focusing or paying attention

- Trouble falling or remaining asleep

- Seeking reassurance

- Rumination (thinking about situations over and over)

- Excessive studying

- Excessive list-making

- Procrastination

- Refusing to go to school

- Tantrums

- Snapping at others

We're Hiring - Apply Now

Quirky Kid continues to grow, develop and evolve. As a result, we have new positions for child psychologists and a mental health clinician (Social Worker, Occupational Therapist, Mental Health Nursing or Psychologist) who shares Quirky Kid’s passion for working with children – Together, amazing things happen.

What are the effects of GAD?

GAD is characterised by almost constant anxiety about a multitude of things. This means children with GAD are dealing not only with worry, but also the emotional and physical symptoms of worry, on a daily basis.

As a result, GAD can have negative consequences on several areas of children’s social, emotional and educational wellbeing (Anxiety Canada, n.d.). While parents of older or very private children may struggle to identify the immediate signs of GAD, they may notice carry-on effects of their child’s anxiety which can alert them to the problem.

The effects of GAD can look like:

- Declining grades due to school refusal or difficulty paying attention in class

- Over-prioritisation of study over recreational activities or spending time with friends due to fear of failure

- Development of depressive symptoms because they are starting to withdraw from friends and family

- Reliance on unhealthy coping mechanisms to escape their anxiety, such as excessive media consumption or substance abuse

What should I do if I think my child has GAD?

If you recognise the signs of Generalised Anxiety Disorder in your child, there are a few things you can do to help:

- Talk to a professional. Speaking with your GP or the Quirky Kid Clinic is a good first step. Other options include your paediatrician or a school counsellor.

- Try talking to your child about how they are feeling. Rather than quickly reassuring them, let them express their worries to you. Being available to listen and showing compassion while exploring what’s on their mind can be helpful. The aim is to support and help your child to self-regulate (rather than managing their anxiety for them).

- Helping your child to reframe their negative thoughts can encourage them to look at a situation or event from a different perspective. You could team up with your child to evaluate their thoughts about an anxiety-provoking situation. Are their thoughts helpful? If not, brainstorm more accurate and helpful thoughts they could replace them with. For example, “I can’t do this, it’s too hard and I'm going to fail,” could be reframed as “Challenges are important for learning. The more I practice, the better I get!”

- Regularly practice simple relaxation techniques. Activities such as controlled breathing, progressive muscle relaxation and mindfulness are shown to be helpful in managing generalised anxiety.

- Check out The Quirky Kid Shop for a selection of useful anxiety resources for parents and children.

Want to speak to a professional? We’re here for you.

The Quirky Kid Clinic is a unique place for children and adolescents aged 2 to 18 years. We work from the child’s perspective to help them find their own solutions. If you suspect your child may be experiencing symptoms of Generalised Anxiety Disorder, you can:

Book an individual session with one of our experienced child psychologists.

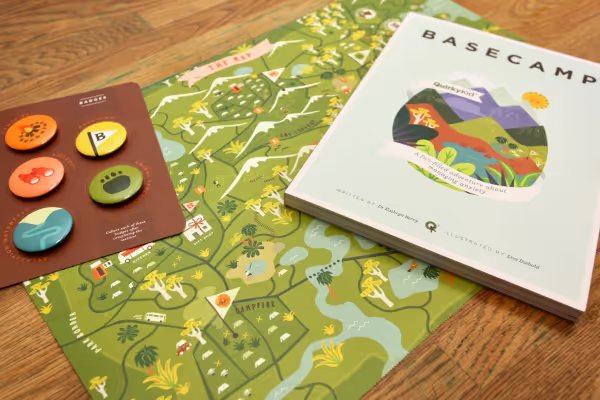

Register for our award-winning child anxiety program - Basecamp.

Contact us for more information.

View article references

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Anxiety Canada. (n.d.). Anxiety in Children. Anxiety Canada. https://www.anxietycanada.com/learn-about-anxiety/anxiety-in-children/

- Anxiety Canada. (n.d.). Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Anxiety Canada. https://www.anxietycanada.com/disorders/generalized-anxiety-disorder-2/

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). ABS National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-survey-mental-health-and-wellbeing-summary-results/latest-release

- Brosschot J.F., & Verkuil B. (2013). Worry. In: Gellman M.D., & Turner J.R. (eds). Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_855

- Centre for Clinical Interventions. (2019). What is Anxiety? Centre for Clinical Interventions. https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/Looking-After-Yourself/Anxiety

- Hartley, C. A., & Phelps, E. A. (2012). Anxiety and Decision-Making. Biological Psychiatry, 72(2), 113-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027

- Songco, A., Hudson, J. L., & Fox, E. (2020). A Cognitive Model of Pathological Worry in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(2), 229-249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00311-7

- Spence, S. H., Zubrick, S. R., & Lawrence, D. (2018). A profile of social, separation and generalized anxiety disorders in an Australian nationally representative sample of children and adolescents: Prevalence, comorbidity and correlates. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(5), 446-460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417741981

- Strack, J., Lopes, P., Estreves, F., & Fernandez-Berrocal, P. (2017). Must We Suffer to Succeed?: When Anxiety Boosts Motivation and Performance. Journal of Individual Differences, 38(2), 113-124. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000228

- Szabo, M. (2007). Do Children Differentiate Worry From Fear? Behaviour Change, 24(4), 195-204. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.24.4.195

- Szabo, M., & Carr, I. (2015). Worry in Children: Changing Associations With Fear, Thinking, and Problem-Solving. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(1), 120-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614529366

- Wilson, C. (2020). Understanding Children’s Worry: Clinical, Developmental and Cognitive Psychological Perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.4324/9781351227667

.png)

.webp)

.png)

.avif)